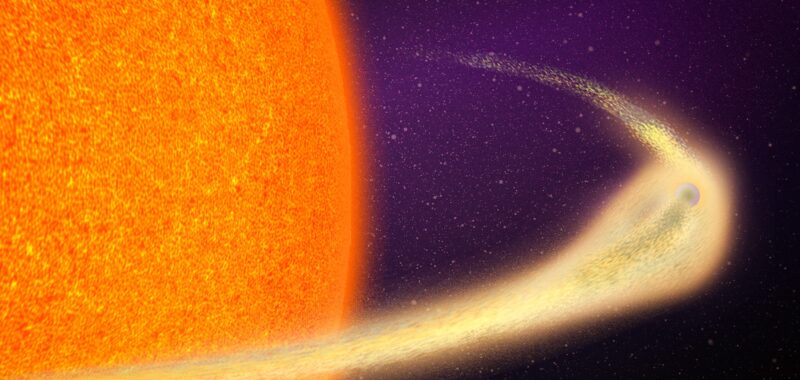

Inside the Pegasus constellation, a planet is disintegrating into boiling chunks of rock and evaporating minerals. Its dramatic final days aren’t due to cataclysmic surface events, but rather the proximity to its star. With a 30.5-hour orbit and a position about 20 times closer than Mercury’s distance to our sun, BD+05 4868 Ab more resembles a comet than a planet, with a debris tail as much as 5.6 million miles long.

“The extent of the tail is gargantuan… roughly half of the planet’s entire orbit,” Marc Hon, an MIT postdoc at the Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, said in a statement.

Discovered by accident using NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), Hon and colleagues detail BD+05 4868 Ab’s final days in a study published April 22 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“We weren’t looking for this kind of planet,” Hon explained. “We were doing the typical planet vetting, and I happened to spot this signal that appeared very unusual.”

An orbiting exoplanet’s signal typically features a brief, regularly repeating light curve dip that indicates it’s passing in front of a host star. BD+05 4868 Ab’s brightness takes much longer to return to its normal measurement. This implies a long, trailing formation that continues to block host starlight. Each orbital rotation’s light dip also varies, indicating that the formation is dynamically shifting in size and composition.

Although the transit shape resembles a long-tailed comet, the composition doesn’t align with that kind of space object.

“It’s unlikely that this tail contains volatile gases and ice as expected from a real comet—these would not survive long at such close proximity to the host star,” said Hon. “Mineral grains evaporated from the planetary surface, however, can linger long enough to present such a distinctive tail.”

Astronomers have only identified three disintegrating planets before BD+05 4868 Ab, all of which were detected over a decade ago using data collected by NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope. The newest find is the most violent example yet, with the longest tail and deepest transits of the four known examples.

“That implies that its evaporation is the most catastrophic, and it will disappear much faster than the other planets,” said Hon.

“Faster” is often relative when dealing with cosmic events, and BD+05 4868 Ab’s case is no exception. Even losing an estimated Mount Everest’s worth of material with every orbit, it will still take 1–2 million years before the planet is completely destroyed. Until then, conditions on BD+05 4868 Ab will remain pretty hellish: surface temperatures reach an estimated 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Such constant, punishing heat also means the entire planet is likely covered in boiling magma as its mineral grains continue to evaporate into space.

“This is a very tiny object, with very weak gravity, so it easily loses a lot of mass, which then further weakens its gravity, so it loses even more mass,” explained Avi Shporer, a study co-author at the TESS Science Office. “It’s a runaway process, and it’s only getting worse and worse for the planet.”

According to Shporer, it’s pure luck that astronomers detected BD+05 4868 Ab when they did.

“We got lucky with catching it exactly when it’s really going away,” said Shporer. “It’s like [it’s] on its last breath.”