Photograph by Erica Maclean.

In the Laurie Colwin novel Family Happiness, a mother and daughter get on the telephone to discuss the menu for an upcoming family dinner—either a roast leg of lamb or roast beef, with potatoes and, the mother says, “those lovely cold string beans of yours for a second vegetable.” Colwin writes: “On both sides of the line, mother and daughter settled down for the conversation they enjoyed most: what to serve with what for dinner.” The two agree to decorate the table with quince branches and have apple pie for dessert. The scene is quintessentially Colwin: it’s relatable, but glamorous too. It paints a picture of a kind of idealized family life that few people actually experience. I’m especially struck by the phrase “second vegetable” and all that it implies about a particular culinary tradition: Some people think two vegetables at dinner is de rigueur, but I’ve encountered those people only in books.

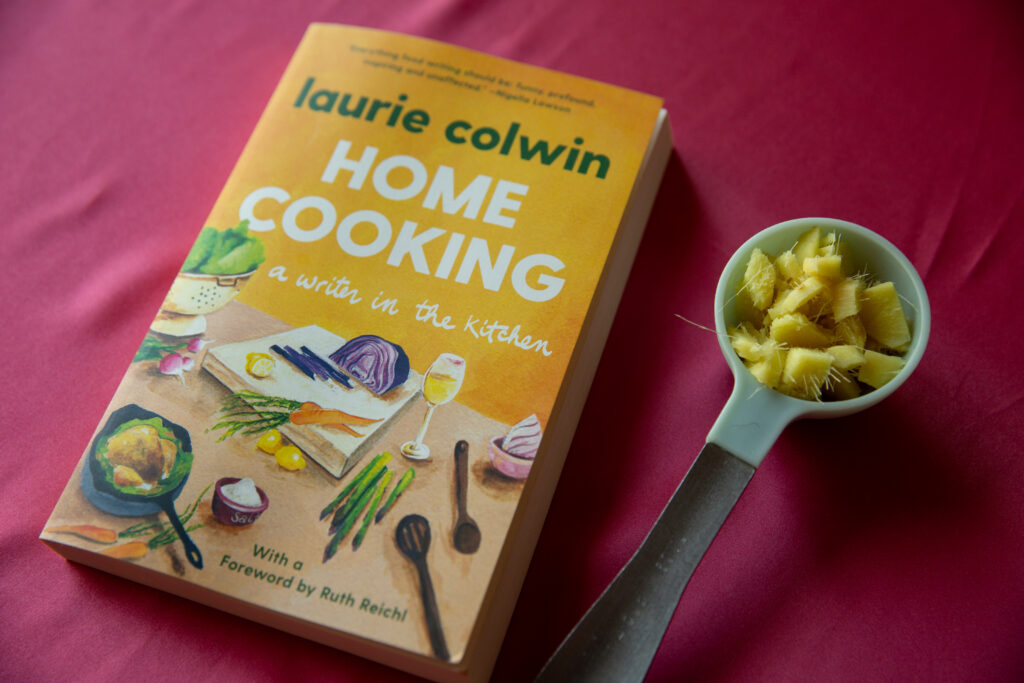

Colwin’s other novels include Happy All the Time and Another Marvelous Thing. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

Colwin, born to an upper-middle-class Jewish family in Manhattan, wrote five novels and enough essays for Gourmet Magazine for two collections of food writing before her death in her sleep in 1992 at age forty-eight from an aortic aneurysm. Home Cooking, one of those collections, has been pressed upon me countless times when people learn I write about food. Despite Colwin’s early death, she has remained in print, and all her books have been recently reissued. Colwin was married to Juris Jurjevics, the founder of Soho Press, and both her adult child, RF Jurjevics, and her longtime friend the writer and academic Willard Spiegelman say that her two interests—fiction and food—were really two facets of an overriding interest in people. She loved to bring people together over dinner, talk to them, and get their life story. “Laurie often had people in the kitchen before a meal, and she would often start her inquiries there,” RF Jurjevics told me recently over the phone. “My father told me that how he knew Laurie was going to begin in earnest was when she would ask her subject, re: their romantic partner, ‘So, how did you two meet?’ ”

Gingerbread in process: my recipe, which is different from Colwin’s, starts out with a liquid batter. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

The idealized domesticity—the mother and daughter on the telephone discussing vegetables—that crops up in Colwin’s work, however, is only the beginning of the story, and was elusive in her own early life. The daughter from Family Happiness, Polly Solo-Miller Demarest, turns out to have been people-pleasing for a lifetime, most especially in her relationship with her mother. Polly wants to have a “perfect” and “effortless” life like the rest of her family, but she is secretly having a tortured affair with a solitary Downtown painter who wears “briary” fisherman sweaters. Colwin’s mother, Jurjevics says, was “difficult.” She was a grande dame who served dinner with crystal, and her relationship with her daughter was “fractious,” added Spiegelman. The family moved around a lot, often living in wealthy, manicured suburbs, which left Colwin feeling suffocated. She became allergic to all forms of pretension, dropped out of college after two years, and set up in a tiny studio apartment with no kitchen sink in Manhattan’s West Village, determined to chart her own course.

My gingerbread cake calls for adding the flour mixture to the wet ingredients—the last step before putting it in the oven and hoping the baking soda reaction doesn’t cause a volcanic overflow. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

Colwin’s food writing was an even more overt way of distinguishing herself from her mother than her fiction was. Her tiny studio apartment features prominently in Home Cooking. She writes about making veal scallops or an ill-fated pot roast for her guests (she could fit three but no more in her apartment) and then washing the dishes in the bathtub afterwards, or serving her home-cooked meals on a folding leatherette card table scarred by a cigarette burn—about as far from white tablecloths and crystal in the suburbs as one could get. The joy of food, and eating food together, Colwin insisted, could be almost entirely separate from status and even one’s material circumstances. Legions of fans have stepped into the kitchen after her, responding to her warmth and approachability.

Wrap the springform pan in tin foil and bake on a baking sheet to prevent overflows. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

I recognize some things about Colwin’s attitude toward cooking. One memory of my childhood is of a special pillow my mother sewed, green, with frogs and stripes, for me to sit on, on the counter, while she baked. This was in a tiny house with a huge yard in Mableton, Georgia, a modest suburb of Atlanta. My mother would talk to me while I sat on the counter, and allow me to taste the cookie batter in its various stages: finished was best, but the curdled step after the eggs went in had a certain intensity. In the late afternoons after baking, if we had time before my father came home from work, she would take me out walking between the towering rows of her vegetable garden and tell me stories: thrilling, terrible stories that starred a larger-than-life villain—her abusive alcoholic father, a big man in a small town in rural Pennsylvania, who beat his children with his belt and punched them with a fist that wore a flesh-cutting class ring. These stories were full of cool fifties cars with custom paint jobs. But when her father came home drunk to beat her mother, she would step in, bait him, draw him off, and bring him onto herself. Her mother was occasionally hospitalized. My mother was—and still is—enormously fiery and brave.

She was also averse to convention. She cooked when she wanted to, cleaned when she had to, made elaborate Halloween costumes, threw crazy kid parties, sold tile murals from a kiln in our backyard. She didn’t want to do anything everyone else was doing; she scorned it. If I told her about my longing for life to look like the happy parts of a Laurie Colwin novel, she’d say, What bullshit, and, Oh please. As a daughter responding to her mother’s character, I—naturally—love it when things are orderly, do serve dinner with crystal, and yearn for the kind of romanticized, conventional, generationally intact family that exists as the ideal in Laurie Colwin novels, even if the real picture is more complicated. I think caring what people think is fine, and even nice, part of living in a shared society. And it’s funny to me how much of my staking-out of my own ground has occurred in the kitchen. I don’t know if daughters always attempt to distinguish themselves from their mothers through their kitchen habits, but I have.

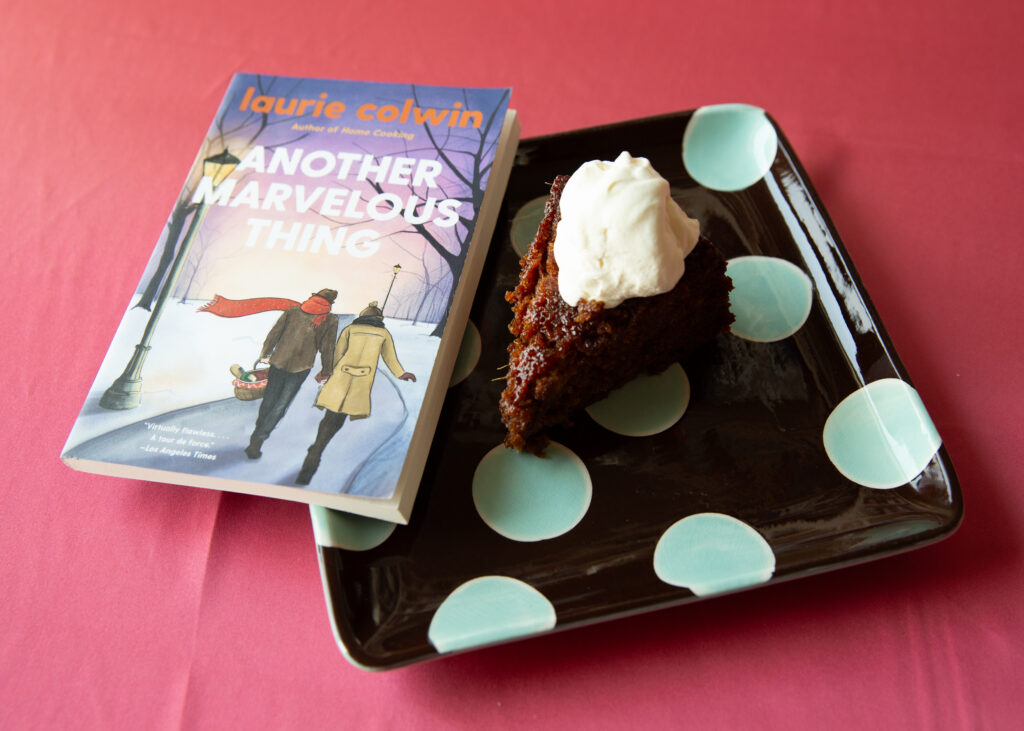

My finished cake is rich, sticky, moist, chewy gingerbread perfection, and has a slightly crunchy top. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

A well-loved recipe from Home Cooking that RF Jurjevics mentions to me is a gingerbread cake with chocolate icing, which Colwin originally made using the tiny baking trays from a toy kitchen of Jurjevics’s childhood. Later, the writer said it was her favorite cake to make for her own birthday. I have a favorite gingerbread cake of my own; in fact, one of the ways I rewrite my unconventional childhood is by having traditional meals—my tart crust, my salad dressing, my hors d’oeuvres strategy (chips! It’s easy, and I think getting people drunk early makes for a better party). I like to imagine, probably delusionally, that people expect these things from me, and that they feel they’re participating in a kind of social order when they come to my house and encounter my elaborately plated dinners and seating cards. I was eager to try my gingerbread cake recipe against Colwin’s, and even a little nervous: it felt like competing with a giant.

Colwin’s batter started out with the butter and sugar creamed together, and was thicker. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

The two cake recipes are very different. Colwin’s is more like a conventional cake. She calls for butter creamed with brown sugar, followed by a specialty ingredient—Steen’s 100 Percent Pure Cane Syrup—and relies on a heaping tablespoon of ginger powder, plus allspice, cinnamon, and clove for the gingerbread flavor. Mine uses Grandma’s Molasses, but calls for some specialty ingredients in the flavoring—an extra-strong ginger root powder I bought at an Indian grocer, plus Chinese cinnamon. I also add pureed ginger root, which really gives a spicy, fresh kick, and use olive oil instead of butter, which creates a deep, sticky, moist texture. My batter is nearly liquid and my cake cooks for an hour. Colwin’s batter is thick, and her cake can take as little as twenty minutes in the oven.

Colwin’s classic gingerbread cake from Home Cooking asks for chocolate frosting, a strange combination that I liked, though not all tasters agree. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

Both cakes were good, but, and I say this with little pleasure, four out of four tasters preferred mine in texture, moistness, and flavor. Having tried several of Colwin’s recipes, I often find them too approachable, even with the occasional niche ingredient like the Steen’s cane syrup to glam things up. (Cane syrup is made from raw pressed cane juice and has a lighter and more delicate flavor than molasses.) Colwin’s style was different from my version of today’s elaborate DIY home cooking, which is generally more laborious but can often be rewarding. My recipe has many more ingredients and steps than hers does, and even requires that the springform pan be wrapped in tinfoil to prevent overflow during the volcanic baking soda reaction that occurs when the batter hits the hot oven.

Dueling specialty ingredients: Steen’s 100 Percent Pure Cane Syrup, which is much milder than molasses; my extremely powerful ginger root powder. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

Polly Solo-Miller Demarest, according to the man she is having the affair with, is “the truest, safest, and most loving person he had ever known.” She may hail from an upper-crust Manhattan setting where the Solo-Millers “dress” for their weekly Sunday breakfast—an environment at times stultifying and intoxicating in its ideal. But Colwin knew that the warmth was the essential part, and it was with this that she approached her kitchen and invited others in. I hope I’m doing the same—plus starched napkins, seating cards, and fancy gingerbread. And if I’m not, my daughter will tell you about it in twenty years.

Laurie Colwin’s Gingerbread with Chocolate Icing

For the gingerbread:

1. Cream one stick of sweet butter with ½ cup light or dark brown sugar. Beat until fluffy and add ½ cup molasses.

2. Beat in two eggs.

3. Add 1 ½ cups of flour, ½ teaspoon of baking soda, and one very generous tablespoon of ground ginger (this can be adjusted to taste, but I like it very gingery). Add one teaspoon of cinnamon, ¼ teaspoon of ground cloves, and ¼ teaspoon of ground allspice.

4. Add two teaspoons of lemon brandy. If you don’t have any, use plain vanilla extract. Lemon extract will not do. Then add ½ cup of buttermilk (or milk with a little yogurt beaten into it) and turn batter into a buttered tin.

5. Bake at 350°F for between twenty and thirty minutes (check after twenty minutes have passed). Test with a broom straw, and cool on a rack.

For the chocolate icing:

1. Cream ½ stick of sweet butter. When fluffy add four tablespoons of unsweetened cocoa.

2. If you have some, add one teaspoon of vanilla brandy (easily made by steeping a couple of cut-up vanilla beans in brandy—another excellent thing to have around), or plain vanilla or plain brandy. Then add about a cup of powdered sugar, a little at a time until you get the consistency you want.

—From Home Cooking by Laurie Colwin

Photograph by Erica Maclean.

Spicy Gingerbread Cake

1 cup boiling water

¾ cup chopped, peeled ginger root

1 cup sugar

1 cup good flavored olive oil

1 cup molasses

2 tsp baking soda

½ tsp salt

2 large eggs, at room temperature

2 cups flour

1 tsp ground cinnamon (or Chinese cinnamon)

½ tsp ground allspice

½ tsp ground cloves

Pinch of ground nutmeg

Pinch of black pepper

Whipped cream to top

Preheat oven to 350°F. Line bottom of a nine-inch springform pan with parchment paper. Grease the paper and the sides with butter. Tightly wrap the outer sides and bottom of the pan in a double layer of aluminum foil, and place on a rimmed baking sheet.

Process one cup boiling water and ginger in a blender until smooth, about one minute. In a large bowl, combine sugar, oil, molasses, baking soda, and salt. Add the ginger water and whisk to combine. Add the eggs and whisk again to combine. Add flour, cinnamon, allspice, cloves, nutmeg, and pepper and whisk to combine. Pour batter into prepared pan, and bake on rimmed baking sheet until a tester inserted in the middle of the cake comes out clean, about one hour. Let cool completely and serve topped with whipped cream.

—Adapted from Bon Appétit

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.