In some orchids, photosynthesis is out and parasitism is in. Instead of making food from sunlight, some of these plants have become parasitic and primarily suck nutrients out of the fungi in their roots. Whether these orchids change their feeding method when they can’t get enough nutrients through photosynthesis alone or if they actually get more nutritional benefits from the parasitism has eluded scientists. New research into the orchid Oreorchis patens shows that it might be the opportunity and not necessity that is driving them. The findings are detailed in a study published February 19 in The Plant Journal.

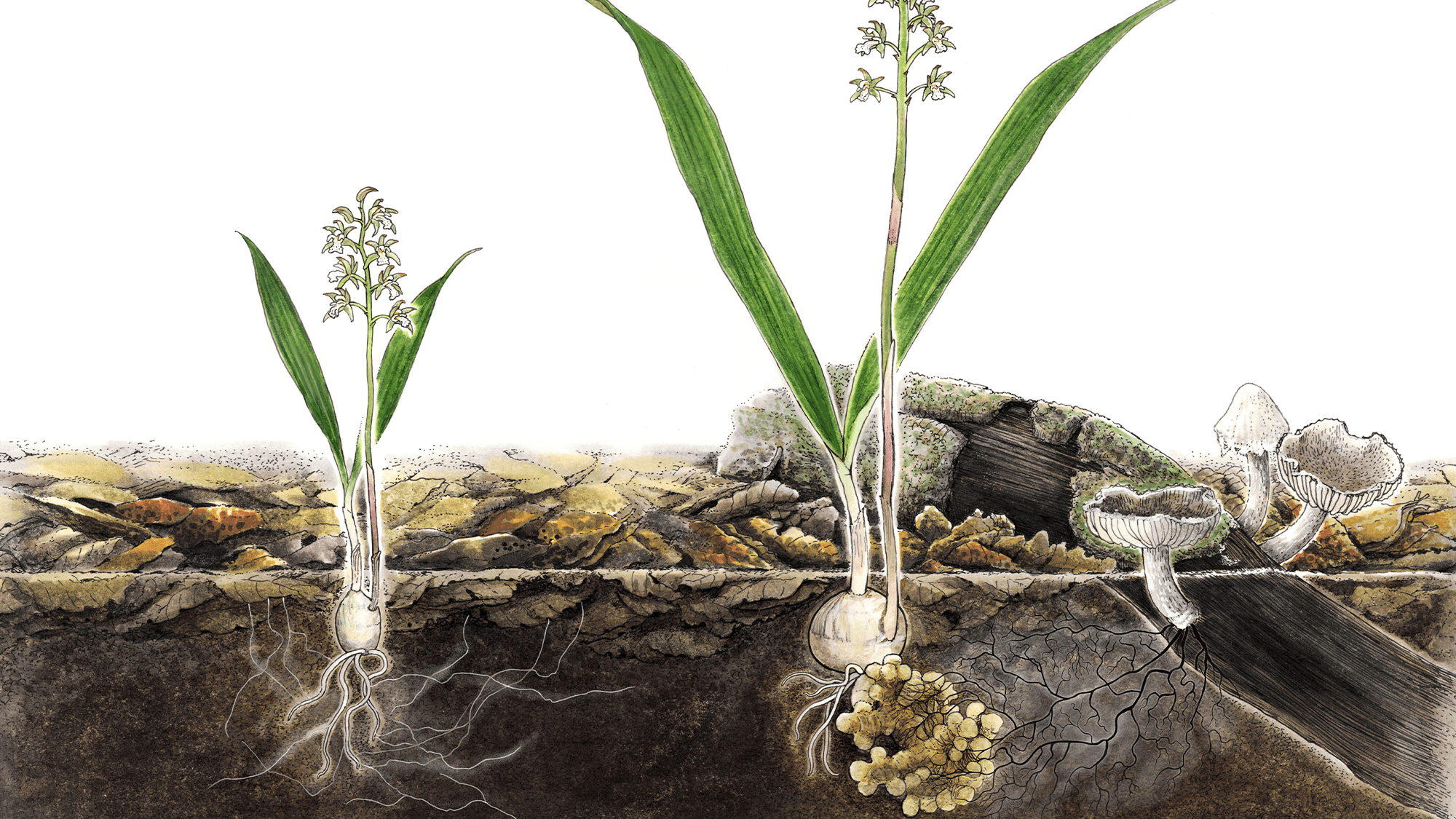

Most orchid species have a symbiotic relationship with the natural fungi found in their roots. The plants provide the fungi with sugar through photosynthesis and the orchids receive important water and minerals from the fungi. However, some have generally stopped photosynthesis and only feed on the fungi instead.

“I’ve always been intrigued by how orchids turn parasitic,” Kenji Suetsugu, a study co-author and botanist at Kobe University in Japan, said in a statement. “Why would a plant give up its reliance on photosynthesis and instead ‘steal’ from fungi?”

In the study, the team looked at Oreorchis patens. This species is common across eastern Asia and is known for iridescent yellow flowers. Oreorchis patens is also considered a partial parasite. It can produce its own food, but also takes up to half of its food budget from fungi. Occasionally, it can grow some strange coral-shaped rootstalks. According to Suetsugu, this trait is more often seen in orchids that fully rely on fungi.

“I thought that this would allow me to compare plants with these organs to those with normal roots, quantify how much extra nutrients they might be gaining, and determine whether that extra translates into enhanced growth or reproductive success,” said Suetsugu.

From June 2010 to November 2021, the team conducted fieldwork in three temperate forests, each with over 100 mature Oreorchis patens. Most of the plants were located near decomposing logs on the forest floor or beneath the litter layer. The team found that when an orchid happens to grow close to rotten wood, it will shift its fungal symbionts into those that decompose wood. This change significantly increases the amount of nutrients that it takes from the dying wood, but does not stop photosynthesis. These plants are often bigger and produce more flowers.

“In short, these orchids aren’t merely substituting for diminished photosynthesis, they’re boosting their overall nutrient budget,” said Suetsugu. “This clear, adaptive link between fungal parasitism and improved plant vigor is, to me, the most thrilling aspect of our discovery, as it provides a concrete ecological explanation for why a photosynthetic plant might choose this path.”

[ Related: These parasitic plants force their victims to make them dinner. ]

However, the question of why less than 10 percent of these orchids exhibit this behavior remains unanswered. In order to become a parasite, the orchids need to switch from their usual symbionts to different fungi in order to handle this increased amount of food. The appropriate fungi only occur around fallen wood and during certain stages of decomposition. So the orchids only become parasitic when they can–and are near the right wood–and not when they need to. This opportunity is also not a lengthy visitor and does not happen often.

Further study could help determine what triggers the orchids to develop these coral-like rootstalks and whether certain environmental factors influence the amount of nutrients that the plants take in from the fungi.

“This work is part of a broader effort to unravel the continuum from photosynthesis to complete parasitism,” said Suetsugu. “Ultimately, I hope such discoveries will deepen our understanding of the diverse strategies orchids employ to balance different lifestyles, thereby aiding in the preservation of the incredible diversity of these plants in our forests.”