My iMac G3, running Warp.

The world’s first screen saver was not like a dream at all. It was a blank screen. It was called SCRNSAVE, and when it was released in 1983 it was very exciting to a niche audience. It was like John Cage’s 4’33″ but for computers—a score for meted-out doses of silence.

Instructions for using the screen saver were first published in the tech magazine Softalk. The headline read: SAVE YOUR MONITOR SCREEN! Across from the article was a full-page photo of firefighters rescuing a computer monitor from a burning building.

Softalk, December 1983.

The article explained that there was a new danger facing computers: “burn-in.” Basically, if a screen showed the same thing for too long, the shadow of its image would be tattooed to the pixels. A screen saver stirs the soup of the image to keep it from sticking to the screen.

The science behind burn-in is grotesque: picture swarms of electrons like locusts flinging themselves at the thin phosphor coating of a screen, chewing holes. A screen saver periodically smokes the locusts out, thereby saving the screen from the disfigurement of monotony.

SCRNSAVE was a big deal engineering-wise, but it never caught on with most computer users, who, reasonably, did not see the value in making their screens shut off every few minutes. Before long, software developers figured out how to convince people to adopt screen savers: aesthetics. The screen savers had to make people want to look back at the screens they had just looked away from.

In 1989, a software company called Berkeley Systems launched a program called After Dark. Instead of just going blank, After Dark screen savers showed animations: flying toasters, or falling rain, or overlapping curved lines in neon gradients. The new screen savers took the world by storm. But in terms of preventing burn-in, flying toasters were no better than a blank screen. Their purpose was pleasure.

After Dark 2.0, Berkeley Systems, 1992.

I don’t know the exact percentage of my life I have spent watching screen savers, but I’m sure it’s equivalent to the amount of time I’ve spent peeing or stuck in traffic. I’ve probably watched screen savers for the same amount of time I’ve spent dreaming about the car, the airplane, and the hill. The details change, but every night for years I’ve dreamed that I’m in a car, and that I’m on an airplane, and that I’m jumping off the top of a hill.

When I was a kid, my favorite After Dark screen saver was called Warp. In Warp, you’re flying into the center of a tunnel of tiny white stars. Nothing happens except that you keep going forward. Nothing changes, but it always seemed to me like it might. Like if I kept looking I might finally see past the tunnel’s center. I’d watch until an adult snapped their fingers in my face and told me to pay attention.

In my least favorite screen saver, 3D Maze, you’re running through a maze with red brick walls and a white asbestos-tiled ceiling. The light is cold and fluorescent, like in an office building. Sometimes you go the wrong way and have to briefly run backward. Sometimes the whole maze flips over and you keep running on the asbestos ceiling like nothing happened. The worst part of 3D Maze was that it could appear on any computer screen without warning. Once the screen saver had started, it was hard to look away, even though I knew what would happen. Every night in my sleep I climb the hill, and I jump off the top.

***

There are no screen savers in pleasureis amiracle by Bianca Rae Messinger. But the poems talk about memory as though time itself were a screen saver—a series of recurring dreams that overlap. Messinger writes:

nothing is transposed so she goes back to sleep with no thinking about

fucking but about water or is it the same object anavenue circles it tying

the new ocean and outside there’s a field which is familiar though

destroyed sometimes she has torun as the water comes fast and tan, so

she steals a car in the next scene like a spaceship so fast

Many words in pleasureis amiracle are merged. They make me think of parataxis, the pushing together of distinct ideas in writing. Messinger imagines parataxis as a physical form of adhesion. Words can stick together, and so can everything else. A new ocean to a familiar field. An image burned into a screen.

By the time I started high school in 2008, the screen saver boom had faded. Bored with the limited options on my white plastic MacBook, I downloaded one called Electric Sheep, whose selling point was that it would never show the same thing twice. Every time the screen saver ran, my computer would connect to other computers on the internet, and together they would make new kaleidoscopic patterns in new kaleidoscopic colors. The website explained:

When these computers “sleep,” the screen saver comes on and the computers communicate with each other by the internet to share the work of creating morphing abstract animations known as “sheep.” The result is a collective “android dream,” an homage to Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

I was excited to be part of an internet of dreaming sheep. But for some reason my computer could never connect. Every day it made the same four patterns in the same four colors. Instead of many sheep remembering many dreams, the screen saver was like one sheep trying to remember one dream and only seeing fragments. A car, an airplane, a hill.

Bianca Rae Messinger believes phone calls are a form of time travel. For Messinger, if it’s morning on one end of the phone, it’s morning on the other. “If you walked to California from New York,” she explained to me once, “it would be morning by the time you arrived, even if it wasn’t when you left.” A voice on a telephone travels close to the speed of light. Ergo, time travel. In pleasureis amiracle, she writes:

wefight in your red car about space,

whether it’s consecutive, you say, whether it’s observatory

no, i say no too as i tend toagree

without wantingto, but yet each

moment feels improvisatory…

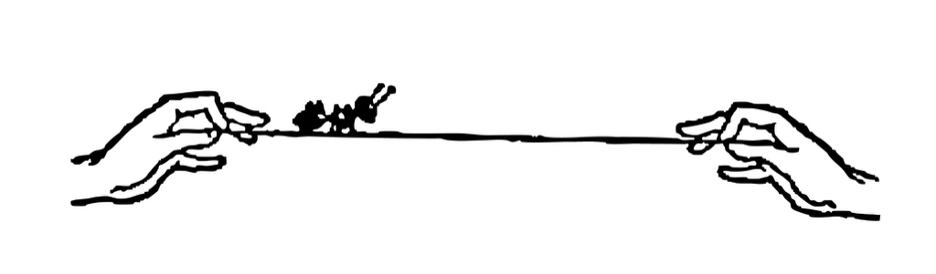

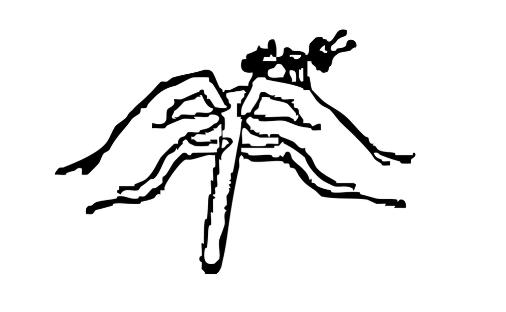

Can time be improvised if we are trapped in it? If we are trapped in time, can we teleport to other places? According to some scientists and science fiction writers, the answer is yes—through something called a tesseract. In A Wrinkle in Time, Madeleine L’Engle describes the tesseract by way of an ant. I’ll summarize:

If an ant wanted to walk from one side of a length of fabric to the other, it would need to walk across the entire surface. Here’s a diagram that L’Engle included in her book:

But what if someone folded the fabric in half? The ant would be able to teleport immediately from one end of the fabric to the other.

Now imagine the ant has been walking along a box instead of a piece of fabric. To travel instantly to the other side, the ant would need to fold the box in half without breaking it, which would mean invoking the fifth dimension: a tesseract.

Are phone calls tesseracts? What about the internet, or dreams? Messinger writes:

doing everything at once doesn’t feel like

an action exactly…this neighborhood

smells like the one I grew up in but

that’s 300 miles away.

pleasureis amiracle asks whether memory is a type of action and whether a repeated action is a form of remembering. The book answers: Memory is an action like the spinning plate of the microwave. It’s morning on both sides of the phone because you remember morning. If you leave a computer awake long enough, it will eventually remember to show a screen saver. Every time it sleeps, the computer dreams its recurring dreams.

***

My grandmother’s iMac spent most of its time showing Flurry, a dancing rainbow spider that was the first-ever Macintosh screen saver when it debuted in 2002. My grandmother was very tech-averse and preferred to write on a yellow legal pad. Whenever she needed to use the iMac, she’d call me with questions. “Thank goodness you picked up,” she’d say. “An alternate universe has emerged in the corner of my screen. Can you help?”

I quickly gave up on trying to convince her to use words like “window” or “application” instead of “planet” or “dimension.” Her descriptions felt closer to the real experience of using a computer—like trying to fly a spaceship. She read a lot of sci-fi. I helped her download Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven from iTunes as an audiobook. We listened together as a man altered collective reality with his dreams.

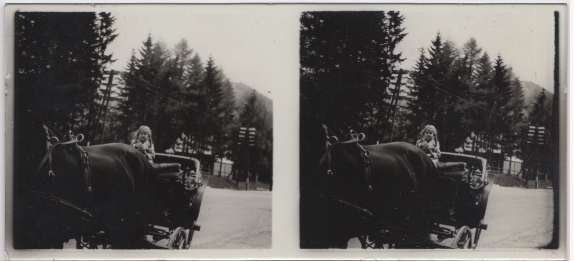

My grandmother’s stereoscope.

A glass slide of my grandmother being pulled by a horse.

One of the few things my grandmother’s family managed to bring from Austria when they fled the Nazis in 1938 was a stereoscope—a three-dimensional image-viewing device. When I was young, my grandmother sometimes let me look through its binocular-like lenses at glass slides of her in Austria: a three-dimensional child in a cart pulled by a three-dimensional horse.

When my grandmother died, everyone agreed I should be given her computer. Actually, at first everyone agreed that we should throw her computer away, but they said I could have it if I really wanted it.

My grandmother’s computer looked like all iMacs had looked for a decade—like a piece of sheet metal with an apple stamped on it. I took it home and it runs decently enough. Not quickly, but respectably. Not quite light-speed, but telephone-speed.

The first iMacs did not look like sheet metal. Instead, they looked like colorful plastic bubbles. I recently bought one on eBay. It’s from 1999 and made of pink translucent plastic—a color Apple called strawberry. My concept was that I’d try and replace my 2021 laptop with the Strawberry. But when the Strawberry arrived, it wouldn’t turn on. When I finally got it to wake up, it could not load most websites.

I took the Strawberry apart thirty-nine times. (I kept count.) I didn’t really know what I was doing. I cut my hands open on the logic board more than once. There’s still dried blood on the hard drive. But despite my best efforts at modernization, the Strawberry has refused to accept any of my updates. It only wants to exist in 1999, to connect to an old internet that hardly exists anymore. These days it mostly runs screen savers. Warp is still my favorite.

The Strawberry and my grandmother’s iMac.

Toward the end of pleasureis amiracle, Messinger writes,

being able to ‘live’ in one’s own memories was what caused

the eventual collapse, and it being joyful. a radio on repeat…

she thinks, an easier way to say this is that dreams are now considered life forms.

I used to think I could use old computers to break open time and get everything back; to fold the screen in two and make a tesseract. I wanted to know what would happen at the end of my dream with the car, the airplane, and the hill. I wanted to go inside the stereoscope and see my grandmother in three dimensions in a place that no longer exists.

But when I finally went back in time, what I found instead were screen savers. Radios on repeat. Places where you could look at time and watch things move around inside it, at the speed of a telephone, just slower than light.

Nora Claire Miller’s debut poetry collection, Groceries, is forthcoming from Fonograf Editions this fall.